Gentle Rifles For Africa? Leave a reply

By Wayne van Zwoll

Dozens of recoil-sensitive hunters return from safaris with the same verdict on rifles and tough game.

When Hemingway and Ruark brought Africa to the page, you’d have taken two or three rifles on safari. A heavy double or bolt-action, perhaps in .500 NE or .416 Rigby, would have seen action only on “big game.” You’d probably have carried a medium-bore bolt rifle, say, a .375, less than your lightweight, scoped 7mm or .30-bore.

These days, few hunters bring three rifles. Doubles are frightfully expensive; bolt rifles dominate for big game. With modern loads, the .375 (in many places the legal minimum for thick-skinned animals) has become a popular “heavy” round. For plains game, you don’t need that horsepower.

Having visited Africa 20 times, I agree with hunters of greater experience that some animals there can be hard to kill. But tenacity is not a function of place; North America has tough animals too. Genetics play into an animal’s ability to endure. So does adrenaline. Gemsbok can take extraordinary punishment, so too blue wildebeest. Pursuit ups the ante, as the will to survive kicks in. But accurate shots always kill.

Gemsbok are tough, but this one folded to a well-placed shot from Cristi’s .308, a Weatherby Camilla.-Wayne van Zwoll

Over the past 13 years I’ve hosted groups of women on their first African hunts, under my

Over the past 13 years I’ve hosted groups of women on their first African hunts, under my

High Country Adventures shingle. “Safari Sisters” who otherwise might never afford such a trip learn of the role of hunting in wildlife conservation. Many “discover” hunting and return as enthusiastic ambassadors.

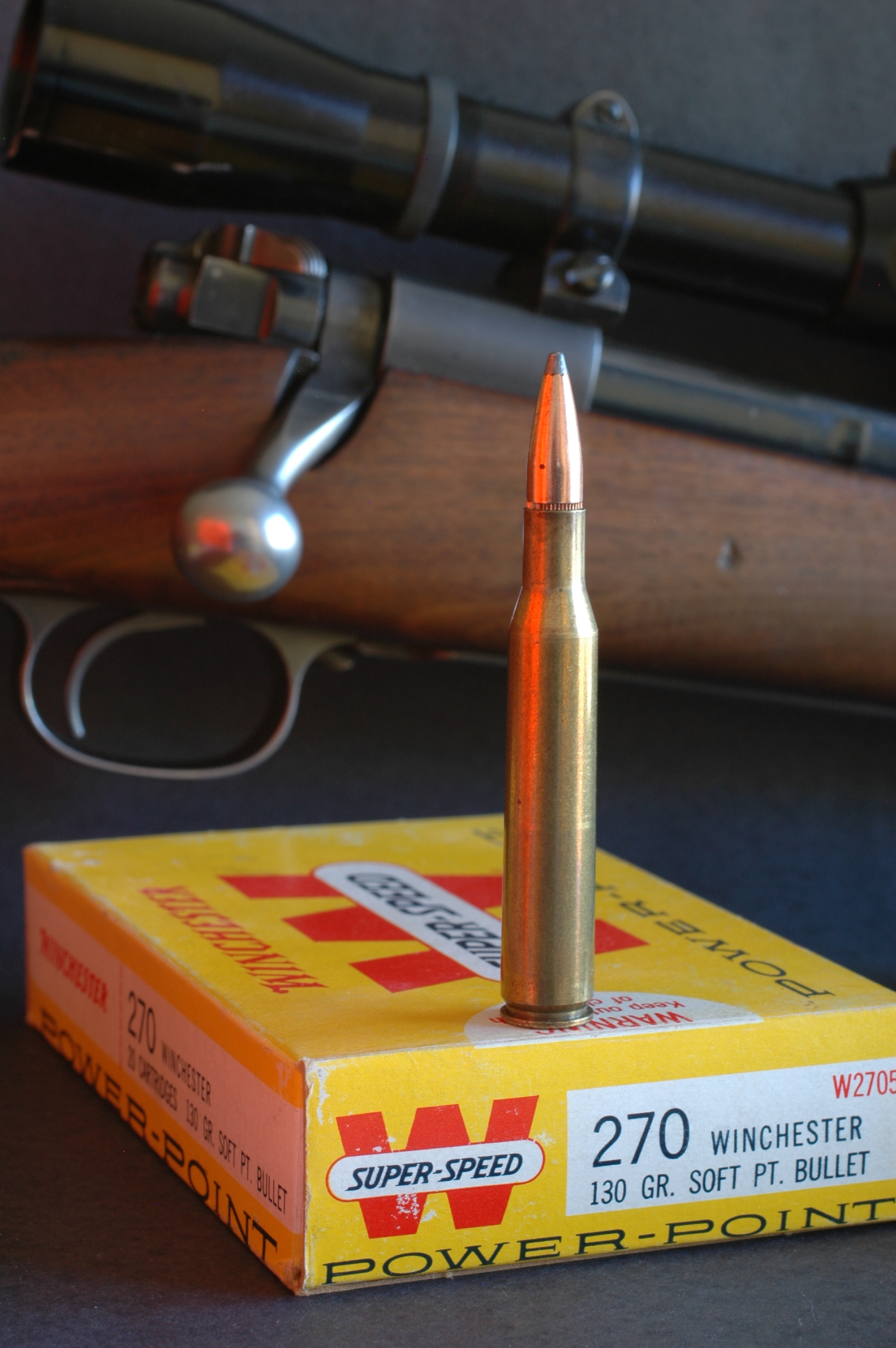

These safari-bound women include some who’ve never fired a rifle. What to use? “A scoped deer rifle works fine,” they’re told. “If you don’t have a rifle, we’ll provide one.” Usually it’s a .308 or a .270.

Is that really enough? Yes. A chest or shoulder hit with those rounds will kill gemsbok and other heavy antelopes as surely as it will deer or elk. To ensure a well-placed shot, Safari Sisters stalk to within 200 yards – and closer. In open country, some sneaks fail. But that’s hunting! The .260, .270 and 7mm-08 routinely drop hardy wildebeest and gemsbok bulls.

Cartridges like the .270 excel on plains game. Safari Sisters also use the .260, 7mm-08, .308, .30-06.-Wayne van Zwoll

Amber brought her 7mm-08, a family gift for the safari. With us, she refined the zero over sticks at paper targets. Her chance at a big warthog required quick shooting. She hit the animal quartering away. It ran just a few yards; but wisely, Amber approached with caution to finish it.

Amber took this tenacious – and trophy-class – warthog with a 7mm-08. Pigs don’t get any tougher!-Wayne van Zwoll

Though a wildlife biologist by profession, Leslie had never shot an animal. Her first kill came at dusk on the hem of thick bush. Suddenly a huge kudu bull ghosted into a gap. Offhand, from sticks, she triggered the .270. The bull leaped, scrambled, and nosed into the sand.

Our youngest Safari Sister, Thea, was slight of build, so borrowed a .270 with a suppressor. She took three animals with three shots, including a fine kudu and a tough blue wildebeest. Her one-shot-kill record was matched by Cathy with a .30-06 and Sara with her .260.

Thea downed this fine kudu with one bullet from a suppressed .270. Gentle recoil! Precise shooting!-Wayne van Zwoll

Tamar liked Africa so much after her first HCA Safari, she’s returned four times, last year taking her husband and son on their first safari. She’s carried her Kimber rifles in .270 and .308 for all the game she’s taken, including an eland that approached a ton in weight.

Lightweight, light-recoiling rifles help hunters get close and fire without flinching. Center hits result!-Wayne van Zwoll

Lightweight, light-recoiling rifles help hunters get close and fire without flinching. Center hits result!These women have in common what most men share but won’t admit: an aversion to recoil. The blast and thrust of a powerful rifle causes flinching. Though I’ve fired rounds as violent as the .338/378 Weatherby and .505 Gibbs from unbraked rifles, I don’t like recoil! No matter your physical build or will to resist flinching, recoil induces reactions you can’t fully erase.

A last-day prize! Emily’s magnificent Namibian kudu fell to a .270 bullet from a Browning rifle.-Wayne van Zwoll

Because they favor rifles gentle in recoil, Safari Sisters can fire without flinching. And they send bullets through the vitals.

W.D.M. Bell, who famously killed elephants by surgically directing bullets from the likes of the 7×57 and .303 British, would have understood – and applauded!

Wayne Van Zwoll

Journalist, Gun Writer

The Outdoor Line

710 ESPN Seattle